Microbiome: the world inside your cat

Study reveals the main biomarkers of the feline microbiota

Vanessa Olszewski¹, Rafaela Hilgemberg², Mariana Nascimento³

¹Veterinary Doctor and Pet Technical Coordinator at Aleris Nutrition

²Zootechnician and Technical Assistant at Sapiens Artificial Intelligence in Microbiome

³Zootechnician and Technical Manager at Aleris Nutrition

A pet nutrition is in constant development and evolution, in order to bring dogs and cats through food, better quality of life energetic longevity.

For some time now, nutrition has no longer been thought of as simply providing food for the survival of animals, but rather as understanding how each nutrient influences at the operation energetic development of the organism.

Following this idea, the search for functional ingredients, which, as the name suggests, will play a role in the body in addition to nourishing. Among them, we can cite as an example the yeast which, depending on the culture medium and processing applied, can offer several benefits. Among these benefits, we can mention the enrichment of the nutritional composition of the feed, helping to increase immunity, agglutination of pathogens, improving palatability and, more recently, it has been understood how it is capable of modulating the microbiome.

The word “microbiome” is commonly defined as “the set of genetic material of all microorganisms living in a defined habitat”. In general, the term “microbiome” covers both bacterial cells itself regarding the your genetic material.

Due to various effects and often deep levels of the microbiome on the health of humans and animals, this came to be recognized as an organ (POSSEMIERS et al., 2011) with exclusive metabolic capabilities, being capable of optimize nutrient digestion and act in postbiotic production, defined, according to the International Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) as a preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that promote benefits to host health (SALMINEN et al., 2021).

The components that may constitute postbiotics, in addition to bacterial biomass, may include organic acids, muropeptides derived from peptidoglycans, structures similar to bacterial pilus (TAKÁČOVÁ et al., 2022), short-chain fatty acids, tryptophan, bacteriocins , among other components and unpurified metabolites (OLESKIN & SHENDEROV, 2019).

Therefore, tutors have a key role in building a beneficial microbiome for your cats through choice of food that will be consumed and the way in which they will take care of your pet's microbiome. However, there is a lack of clear understanding of the impact these food choices have on the microbiome and, therefore, the general health of the animal.

Food for pet animals, in general, is formulated to contain typical nutritional components such as carbohydrates, proteins and fats, but must include microbiome-targeting ingredients, such as prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics. Each of these categories, as well as their relative proportions in foods, can influence the composition and, consequently, the functions performed by the microbiome.

FELINE INTESTINAL MICROBIOTA

To help us begin to build this thinking, did you know that much scientific evidence has already been published indicating that dietary components have the power to impact not only the gastrointestinal diseases, but also the allergies, The oral health, control of the Weight, O diabetes and the kidney diseases of your pet, “only” modulating his gastrointestinal microbiome? Interesting, right?

In the beginning, many efforts to understand the microbiome focused on characterizing changes in microbiome composition in disease states. However, today we have come a long way and are focusing more and more efforts on understanding how composition and combination of ingredients in a food they can influence the health of animals company, through the modulation of the microbiome.

There is enormous value in characterize the profile of animals in healthy state is at disease state. Understand who the main groups that are making up that ecosystem and how are they interfering with the cat's physiology It is a very important step towards developing increasingly assertive solutions that could lead to the microbiome profile of a sick animal being modulated in order to get closer to the profile of a healthy animal, for example.

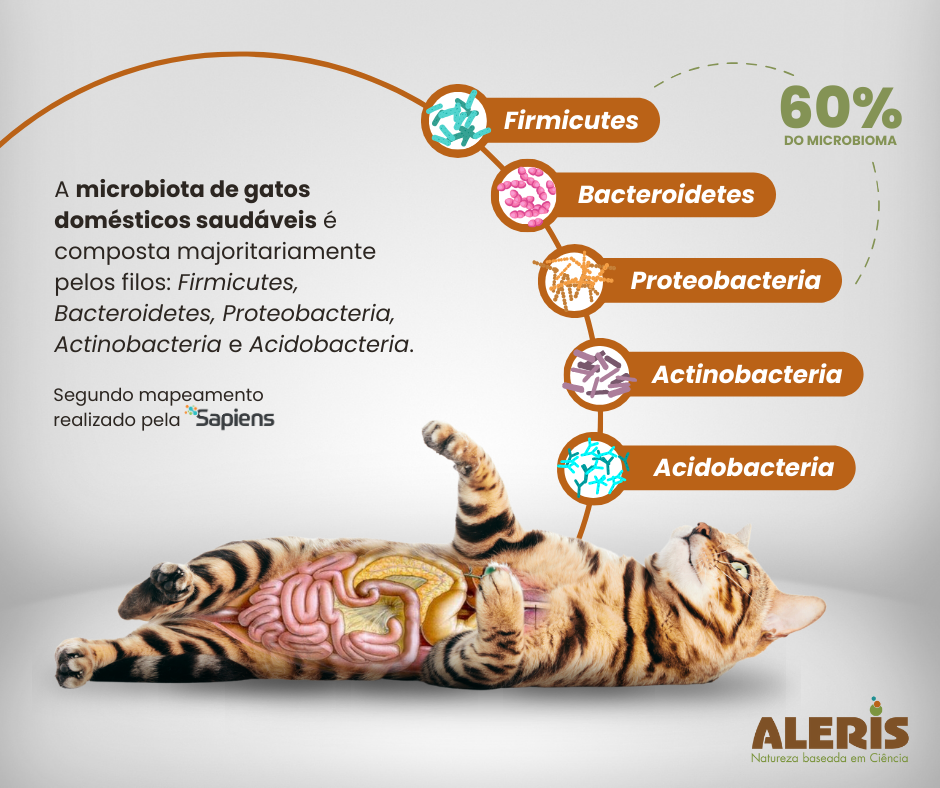

Practically an episode of a journalistic report: Microbiome: Who are they? What and how do they feed? How do they behave? In this way, as in other animal species, the microbiota of healthy domestic cats also is being mapped for the Sapiens and we notice that it is mostly composed by phyla: Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria energetic Acidobacteria. The first three represent approximately 60% of the microbiome. These data agree with other researchers. Research characterizes the microbiome of these animals and describes the phyla Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria as the majority in the microbiota of healthy cats (BARRY et al., 2012; MINAMOTO et al., 2012).

Understanding who these groups are and their abundance in the microbiome helps us understand how diversity and richness can impact the well-being and health of felines. It is a symbiotic relationship between the animal and its microbiome, which is capable of facilitate the digestion of nutrients and from fermentation, produce metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), secondary bile acids, vitamins (SCHMITZ & SUCHODOLSKI, 2016), nutrients and other compounds derived from bacteria (MONDO et al., 2019). The microbiota still influences immune cells and the inflammatory functions (TIZARD & JONES, 2017).

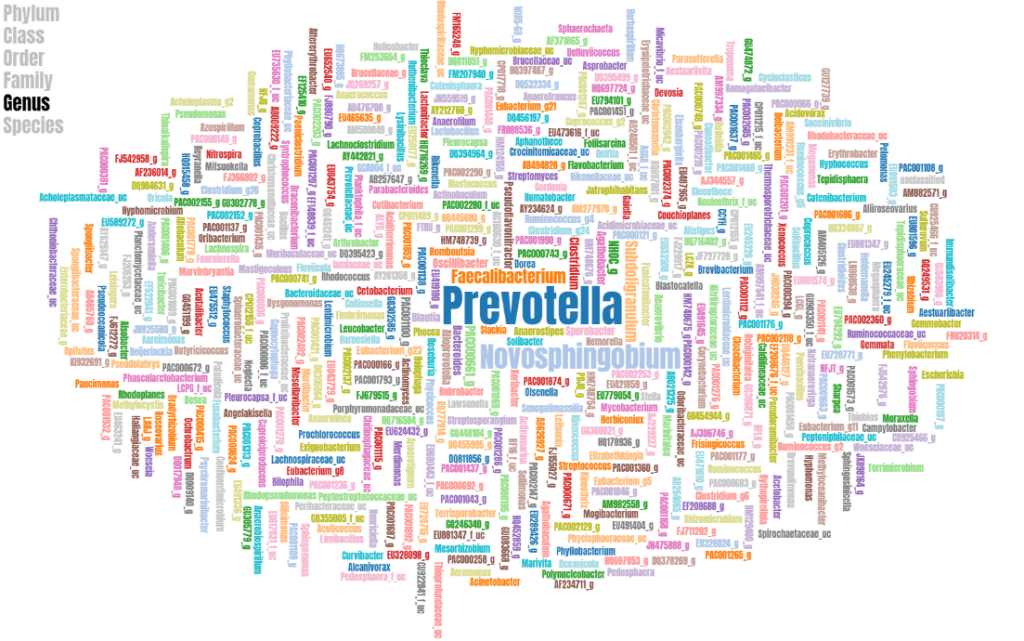

A visual way to begin this understanding is through word clouds. In figure 1, we visualize the Gut microbiota word cloud of healthy cats. In it, we can observe the genera present in the microbiota, where the larger the word size, the more abundant that particular genus is in the microbiota.

Directing our gaze to the composition of genres, according to the database of Sapiens, we observed that cats considered healthy present a greater abundance in Prevotella, Novosphingobium energetic Faecalibacterium. Among these genres mentioned, the Prevotella is the most abundant genus and is closely linked to the largest microbiota robustness against the entry of possible pathogens (AMAT et al., 2020).

Figure 1. Intestinal microbiota of healthy cats. Source: Sapiens database, 2022.

Although understanding the microbiome-based healthcare concept (STALEY et al., 2018) and microbiome diagnoses are not yet widespread, knowledge of who the healthiness biomarkers and specific diseases can increase the effectiveness and efficiency of diagnosis, progression assessment and prognosis (DAVIES, 2018) and become a valuable tool for choosing the most appropriate nutritional therapy.

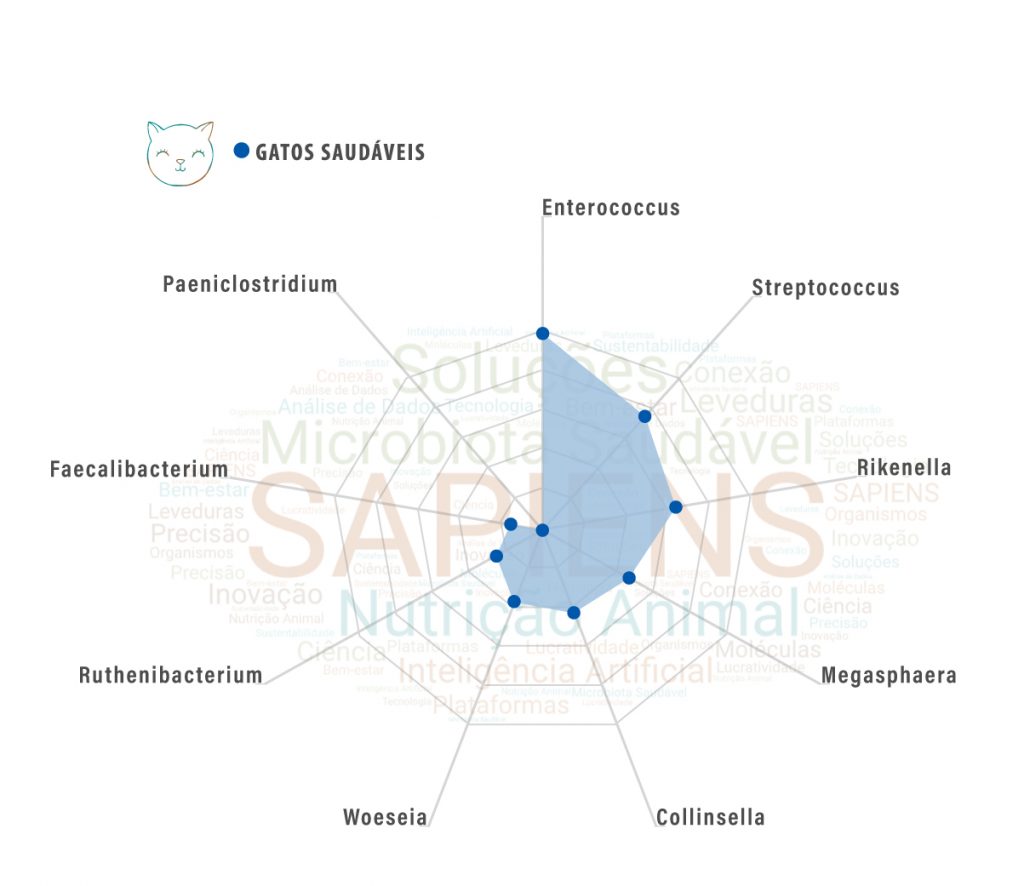

However, the first steps are already being taken, such as (1) characterization of the microbiome, (2) understanding of microbiome-host functions and interactions and (3) identification of biomarkers. In the graph below you can see some biomarkers already identified in the database of Sapiens. And their identification and understanding bring us several interesting insights.

Cats, because they are carnivorous animals, present a profile of microbiome A little different those that we identify in omnivorous or herbivorous animals.

It is very interesting to note that in the cat profile we find a higher percentage of biomarkers that have the versatility in ferment both carbohydrates and proteins – like gender Woeseia, for example – being highly specialized in recycle nitrogen, carbon and sulfur compounds, which are products of protein digestion and fermentation.

The cat microbiome also appears to be better prepared to deal with high concentrations of lipids in the diet. They present clusters of biomarkers that actively participate in lipid metabolic pathways, acting to optimize these pathways and improving the cat's energy use systems.

As you can understand, knowing biomarkers gives us concrete basement and lots of insights for develop food increasingly directed towards the microbiome, aiming to modulate groups that can directly impact the health and well-being of these animals, but more research is needed to deepen and demystify the influence of yeasts and postbiotics on microbiota modulation feline and animal health as a whole.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

ALESSANDRI, G. et al. Deciphering the Bifidobacterial Populations within the Canine and Feline Gut Microbiota. [sl:sn]. Available at: https://journals.asm.org/journal/aem.

AMAT, S. et al. Prevotella in pigs: The positive and negative associations with production and health. Microorganisms. MDPI AG, 1 Oct. 2020.

AQUINO, AA Dry extract of yeast cell wall in diets for adult cats, 2009. 171.f. Thesis (doctorate in zootechnics) – Federal University of Lavras, Lavras, 2009.

BARRY, KA, MIDDELBOS, IS, VESTER, BOLER, BM, DOWD, SE, SUCHODOLSKI, JS, HENRISSAT, B., COUTINHO, PM, WHITE, BA, FAHEY, GC JR, SWANSON, KS Effects of dietary fiber on the feline gastrointestinal metagenome. J Proteome Res. 2012 Dec 7;11(12):5924-33. doi: 10.1021/pr3006809. Epub 2012 Nov 5. PMID: 23075436.

BELL, E.T.; SUCHODOLSKI, JS; ISAIAH, A.; FLEEMAN, L.M.; COOK, A.K.; STEINER, JM; MANSFILD, CS Faecal microbiota of cats with insulin-treated diabetes mellitus. PLOS One, v.9, n.10, p.1-12,2014.

DAVIES, R. (2018). The metabolomic quest for a biomarker in chronic kidney disease. Clinic. Kidney J. 11, 694–703. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfy037

LEDERBERG, J., AND MCCRAY, AT (2001). 'Ome Sweet' Omics—a genealogical treasury of words. Scientist 15:8. doi: 10.1089/clinomi.03.09.05

MINAMOTO, Y., HOODA, S., SWANSON, KS, SUCHODOLSKI, JS Feline gastrointestinal microbiota. Anim Health Res Rev. 2012 Jun;13(1):64-77. doi: 10.1017/S1466252312000060. PMID: 22853923.

MONDO, E., MARLIANI, G., ACCORSI, PA, COCCHI, M., DI LEONE, A. Role of gut microbiota in dog and cat's health and diseases. Open Vet J. 2019 Oct;9(3):253-258. doi: 10.4314/ovj.v9i3.10. Epub 2019 Sep 1. PMID: 31998619; PMCID: PMC6794400.

OLESKIN, AV, SHENDEROV, BA Probiotics and Psychobiotics: the Role of Microbial Neurochemicals. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2019 Dec;11(4):1071-1085. doi: 10.1007/s12602-019-09583-0. PMID: 31493127.

POSSEMIERS, S., BOLCA, S., VERSTRAETE, W., AND HEYERICK, A. (2011). The intestinal microbiome: a separate organ inside the body with the metabolic potential to influence the bioactivity of botanicals. Phytotherapy 82, 53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.07.012

SALMINEN, S., COLLADO, MC, ENDO, A. et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 18, 649–667 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-021-00440-6

SANTOS, JPF Effects of increasing levels of yeast cell wall on digestibility, fecal microbiota and intestinal fermentation products in diets for adult cats. 2015.91 p. Thesis (doctorate in science) – University of São Paulo – Pirassununga.

STALEY, C., KAISER, T., AND KHORUTS, A. (2018). Clinician guide to microbiome testing. Dig. Dis. Sci. 63, 3167–3177. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5299-6

SUCHODOLSKI, J.S., CAMACHO, J., AND STEINER, J.M. (2008). Analysis of bacterial diversity in the canine duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon by comparative16S rRNAgene analysis. FEMS. Microbiol. Ecol. 66, 567–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00521.x

SCHMITZ, S., SUCHODOLSKI, J. Understanding the canine intestinal microbiota and its modification by pro-, pre- and synbiotics – what is the evidence? Vet Med Sci. 2016 Jan 11;2(2):71-94. doi: 10.1002/vms3.17. PMID: 29067182; PMCID: PMC5645859.

TAKÁČOVÁ, M., BOMBA, A., TÓTHOVÁ, C., MICHÁĽOVÁ, A., AND TURŇA, H. (2022). Any future for faecal microbiota transplantation as a novel strategy for gut microbiota modulation in human and veterinary medicine? Life 12:723. doi: 10.3390/life12050723

TESHIMA, E. Therapeutic aspects of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics. In: FERREIRA, CLLF Prebiotics and probiotics: update and prospecting. Viçosa, p.35-60, 2003.

TIZARD, IR, AND JONES, SW (2017). The microbiota regulates immunity and immunological diseases in dogs and cats. Vet.Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 48, 307–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2017.10.008